(Note: the table and figure were not included in the version published in Local Transport Today)

In

my home city of Bristol, critics of the Cycling City

programme have been confounded by a two-thirds increase in the modal

share of

cycling. London has

also seen a similar

increase in cycling, but from a lower base.

High rates of cycling are concentrated in a few Inner

London boroughs plus

the one outer borough of Richmond-upon-Thames.

|

Driving |

Passenger |

Bus |

Train/Metro |

Cycle |

Walk |

|

|

England

2011 |

60.1% |

5.5% |

8.2% |

10.2% |

3.2% |

10.9% |

|

England 2001 |

60.5% |

6.7% |

8.3% |

8.1% |

3.1% |

11.0% |

|

London 2011 |

29.1% |

1.9% |

15.0% |

38.4% |

4.3% |

9.0% |

|

London 2001 |

36.7% |

2.7% |

12.2% |

33.9% |

2.5% |

9.2% |

|

Bristol

2011 |

51.9% |

5.2% |

10.3% |

2.2% |

8.2% |

20.2% |

|

Bristol 2001 |

54.6% |

6.8% |

13.6% |

1.0% |

4.9% |

16.8% |

|

Sustainable Travel Demonstration Towns |

||||||

|

Darlington

2011 |

64.6% |

7.4% |

7.5% |

1.9% |

2.6% |

14.0% |

|

Darlington 2001 |

61.1% |

8.8% |

11.1% |

1.3% |

2.4% |

12.9% |

|

Peterborough

2011 |

62.7% |

9.3% |

8.0% |

2.7% |

6.2% |

9.3% |

|

Peterborough 2001 |

62.4% |

8.5% |

7.1% |

2.4% |

8.3% |

9.2% |

|

Worcester

2011 |

64.1% |

6.2% |

4.9% |

2.0% |

4.6% |

16.7% |

|

Worcester 2001 |

63.0% |

7.7% |

4.9% |

1.5% |

5.1% |

15.9% |

(From

Census Table

CT0015. Home workers, non-workers and other modes excluded)

More

worryingly, the three Sustainable Travel Demonstration

Towns (STDT) Darlington, Peterborough and Worcester have all bucked the

national trend, registering increases in the share of driving to work. The English STDT programme

which ran from

2004 until 2008 was one of the biggest smarter travel experiments

conducted

internationally. Each of the three towns took

a slightly

different approach, but area-wide personalised travel planning was

central to

all of them. The

evaluation study commissioned

by the DfT (Sloman et al 2010) concluded that the programme had been a

success,

with car trips falling by 9% across the three towns, mainly due to

modal shift.

LTT

readers may remember the controversy last year about the

DfT’s treatment of smarter choices in its WebTAG guidance (Issue 598). Implicitly repudiating the

findings of its

own study, the DfT’s modellers opted for scepticism, downplaying the

likely

impact of smarter travel measures.

This

prompted the Campaign for Better Transport to publish alternative

guidance,

using more optimistic assumptions consistent with the various

evaluation

studies.

Central

to that debate was a difference of opinion about the

reliability of ‘before and after’ evaluation studies.

Many studies worldwide have attributed

significant changes in travel behaviour to smarter choices (or

‘Voluntary

Travel Behavior Change’). Most

of these

have relied heavily on before and after surveys.

An influential strand in the academic

literature has questioned the reliability of such methods. However carefully the data

is collected, the

responses may be vulnerable to several types of bias, particularly

social

approval bias and differential response bias i.e. those people who have

a

positive change to report are more likely to respond to a survey than

those who

feel the whole thing has been a waste of time.

Face to face collection methods may minimise the latter,

but increase

the risk of social approval bias.

These

problems may afflict survey-based evaluations of any transport change,

but

those involving social marketing are likely to be particularly

vulnerable: more

so in the ‘after’ surveys than the ‘befores’.

As the evaluations are generally trying to measure small

differences

between two larger figures, even a small bias can significantly skew

the

results.

It

is easy to demonstrate some of these biases in laboratory

situations but how significant are they in practice? This is a

difficult

question to answer: it would require a comparison between survey

responses and

“the right answers” obtained by other, more ‘objective’ methods. Traffic flows are often

measured as well and

they usually ‘tell a different story’.

In the STDT evaluation the traffic counts showed smaller

reductions than

the surveys suggested. The

authors

attributed these differences to a range of local factors such as

population

growth and differences between local and externally-generated traffic. Other studies worldwide

have referred to

issues such as weather conditions on the data collection days. As the surveys and traffic

counts are not

measuring the same things, it is difficult to say with any confidence

whether

the survey measures are telling a true story or not.

The

STDT evaluation showed relatively small changes in

commuting by residents of the three towns.

The modal share of driving fell by 3% in Darlington and

Peterborough,

with no change in Worcester. In

estimating the cost benefit ratios of the STDT programme, Cairns et al

estimated that the effects of the changes would ‘decay’ at a rate of

40% a year

once the programme finished, so we wouldn’t expect much effect to

remain by the

time of the Census. Many

other factors

could have contributed to those increases in driving, which might have

been

greater if the STDT had never happened.

But the simple fact that driving went up may, nonetheless,

strengthen

the hand of the sceptics in the DfT and the Treasury.

The

English STDTs were followed by similar programmes in

Scotland and most recently in the Republic of Ireland, where

implementation

began in Limerick, Dungarvan and Westport last year.

UWE was part of a consortium led by Irish

consultants Transport and Innovation, which bid for the evaluation of

that 5

year programme. The

tender feedback

showed that we scored highly on methodology but narrowly lost out on

price (a

familiar experience to any of you?)

Amongst the ideas we proposed in that tender was one which

could have

helped to resolve those lingering uncertainties about the reliability

of before

and after surveys.

Academics

sometimes jealously guard their untried ideas, but

as we didn’t get the chance on that occasion, I would like to hear from

anyone who

might be interested in trying the following idea in a real situation. This could relate to

smarter choices or any

other change in travel behaviour over time.

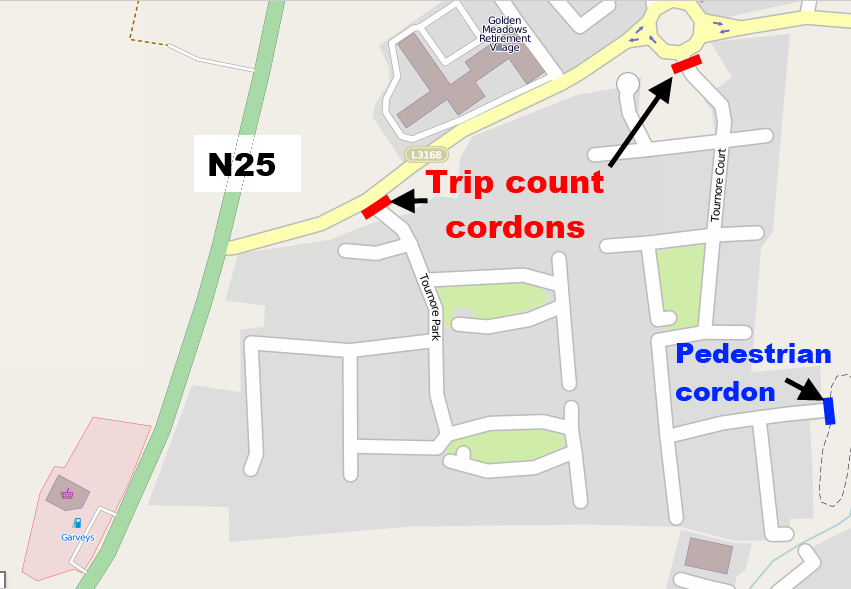

The first step is to identify self-contained networks of residential streets, where all movements in and out can be measured by trip counters or manual observations. Most towns and cities do have such areas, like the ones below which we identified in Dungarvan.

DUNGARVAN MAP (From Open Street

Maps)

Their

populations may not be typical of the whole town, but

that does not necessarily matter.

Within

those areas a higher concentration of households will be asked the same

questions as households across the rest of the town.

These must ask about visitors and deliveries

as well as trips by household members.

The traffic counts should cover the same time periods as

the survey

responses, so self-reported trips can be compared to the traffic

movements. The two

measures are unlikely

to yield exactly the same results.

If we

assume the trip counters measure ‘actual trips’, the key question is

whether

the ratio of reported to actual trips significantly changes between the

before

and the after survey. If

it does, then

adjustments can be made to the findings for the whole town. The devil is often in the

detail when

designing a research study: there would be several practical

challenges, but

none of them seems insurmountable.

Which

modes can be compared in this way would depend on the trip recording

methods:

even if limited to cars and delivery vehicles, it could still help to

verify

the validity of the survey.

Accurately

measuring behaviour change is one challenge.

Explaining the causes is a tougher one.

Why was the Cycling City in Bristol

apparently so much more successful than the STDT programme? It would be

interesting to hear the views of transport planners working in those

three

towns. A number of

studies are looking

at different aspects of cycling in Bristol, which may reveal more. In the meantime, some more

general, and

fundamental, comments can be made.

The

Cycling City programme in Bristol spent considerably

more on infrastructure than marketing.

It accelerated a programme of cycle route construction

already underway,

which is continuing in several places across the West of England area

at the

moment. Much of the

marketing effort was

aimed at promoting these routes, which have gradually joined up to

create one

of the most comprehensive radial networks of any British City. From where I live in the

Centre, I can now

leave the city on cycle routes in six directions: not all off-road, but

joined-up and avoiding heavy traffic.

The design quality is variable – Copenhagen or Groningen

it ain’t – but the

network has created many useful short-cuts for cyclists and pedestrians. For all its faults, I have

watched a growing

number of cyclists and pedestrians using these routes, particularly at

peak

times: the trip counts on one of the most improved routes doubled

during the

Cycling City programme. Some

of the

marketing did help spread awareness of these routes, though much still

remains

to be done in that respect.

Part

of the credit must be given to First Group, for pricing

people off their buses (recently acknowledged with a ‘fares

consultation and

review’ launched under political pressure).

But the fall in bus use is only part of the story: walking

has increased

and car driving has also fallen. Congestion is a problem for cars and

buses, but

a long-standing one: average traffic speeds have been increasing in

recent

years. And I have

witnessed the growth

amongst certain segments of Bristol’s population of a ‘cycling culture’. As one participant in a

focus group put it:

“cycling is not seen as bizarre in Bristol”.

Several analysts of cycling in Northern Europe (e.g.

Pucher, Buelher,

Hembrow) have described how cycling cultures have developed in

countries and

cities where sustained improvements have been made to cycling

infrastructure. To

prove what caused what (or calculate meaningful

cost-benefit ratios) would be impossible, but to surmise that each

reinforced

the other is probably a safe bet.

There

is a broader lesson here for smarter choices and modal

shift. Social

marketing can help to

foster, or accelerate transport cultures of one kind or another. But marketing is about

more than information

or persuasion: it is also about the nature of the product itself. Marketing a useless

product is a waste of

time and money. Fostering

cultural

change where conditions are improving is the only way smarter choices

will work

in the longer-term. If

commissioners of

research are interested in achieving

value for money, rather than simply estimating it, then understanding

how to

foster those changes would be more useful than obsessing about

cost-benefit

ratios for measures which may be impossible to disentangle.