The environment comes first, so we must drive down transport CO2

Local Transport Today, March 18th 2016

The environment comes first, so we must drive down transport CO2Local Transport Today, March 18th 2016 |

|

The interview with Benny Peiser of the Global Warming Policy

Forum in LTT 691 raises some interesting points which merit a response. Peiser, it seems, is not a ‘climate change

denier’; he accepts the underlying science – that greenhouse gases trap heat

and that human activities are generating those gases. The graph that accompanied his article shows

average global temperatures continuing to rise, though not as quickly as some

climate models had predicted. The crux

of his argument is that the rate of change may be slower and the consequences

more benign than the scientific consensus projects. To make costly changes in response to

projected climate change would therefore waste money and cause unnecessary

economic disruption.

The Stern report offers one possible response to that

argument; Stern calculated that action would be much cheaper than inaction in

the long-term. Both of these lines of

argument rely on uncertain predictions about the future, so the debate is

really about how we respond to uncertainty.

This is where transport professionals may legitimately get involved.

There are broadly three types of evidence on climate change:

the basic science, the measurements and the projections of climate models. The level of certainty is highest for the

basic science and lowest for the projections of the future. Between those two, the data on greenhouse

gases are as accurate as the measuring equipment. Likewise with temperatures, although the

averaging process introduces further uncertainties, which explains some of the

variation in global temperature series.

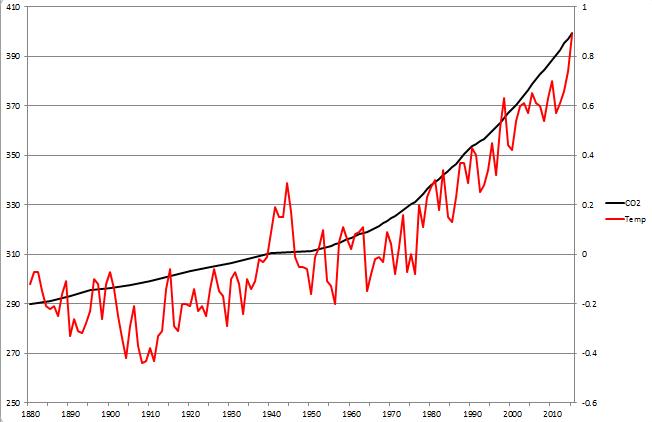

Graph: Atmospheric CO2

(left scale, ppm), Annual global temperature anomalies (right scale oC). Source: IPCC (CO2 to 2010) NAOO (CO2

2010 – 2015 and temperatures)

The graph above shows the concentration of CO2

and changes in average global temperature, taken from the websites of the IPCC

and the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. If anyone believes there has been a global

conspiracy to misrepresent the data, I would recommend they read the Final Report

of the Independent Climate Change E-mails Review, which followed the

‘Climategate’ hacking incident. Look at

the methodology they used. Instead of

trying to unpick the original analysis the panel ran their own analysis using

publically-available temperature records, created by different organisations in

different parts of the world. The graph

on page 47 shows that even if Prof. Phil Jones had been part of a conspiracy

with the IPCC, Al Gore and Al Qaeda to bring down Western civilisation anyone

with the software skills, using different data sources, would have come to

broadly similar results, differing slightly depending on which data source is

used. If you don’t believe that, you can

do it yourself.

More fundamentally, would a conspiracy change the basic

science? Would it change the concentration of greenhouse gases in the

atmosphere? The modelling projections are subject to uncertainty; would a

conspiracy change that fact?

The twin elephants in this room are political values and

‘the evidence we want to believe syndrome’.

We all prefer to believe evidence that supports our world view or

contradicts people we dislike but that does not change the evidence

itself. The Global Warming Policy Forum

clearly places a higher weight on economic growth than they do on environmental

sustainability. They prefer to believe

that global warming will be slow and benign.

I believe that protecting the planet is more important than economic

growth; I don’t believe humans should be changing the composition of the

atmosphere, even without climate change.

I might be tempted therefore to believe more catastrophic projections

but I am not a climate scientist and neither is Benny Peiser or Lord

Lawson. None of us knows how quickly and

in what way the Earth will warm in response to what level of carbon emissions. The science is evolving all the time but

certainty only comes in retrospect. So

when deciding what to do about it we have to invoke the precautionary

principle.

Although Peiser doesn’t actually use that term, he applies

that principle to the economy, which he places above environmental

concerns. I would reverse those

priorities and attach a particularly high weight to avoiding catastrophic

change, even if the likelihood is small and even if (as seems likely) the worst

consequences occur in the distant future.

The predictions of the climate models vary (which is difficult to

reconcile with the idea of a conspiracy) and some or all of them may prove to

be quite misleading but for predicting future consequences, they are all we

have to go on. If the Global Warming

Policy Forum can provide a better method of doing that, they should publish it

for scientific scrutiny.

When considering the implications of all this for transport,

there are many reasons for moving away from fossil fuels and towards more

active travel, such as local air pollution, energy security and public

health. If you believe those reasons are

valid then climate change simply adds urgency to them.

“Every scientist is a layman in another’s field” a physicist

friend once explained to me and that is a useful maxim for this debate. Transport professionals would be well advised

to leave climate science to the scientists.

We may refer to it but if we try to second-guess projections or causal

explanations then we are deluding ourselves and others. On this and on many other issues (speed

cameras, for example) where we differ on policy prescriptions because of our

values or political beliefs then let’s openly acknowledge that, instead of

trying to hide behind different and sometimes dubious interpretations of factual

evidence.

Dr Steve Melia is Senior Lecturer in Transport and Planning

at the University of the West of England and author of Urban Transport Without the Hot Air.