In 1995, when Sustrans’ first application for the National Cycle Network was approved it was Paddy Ashdown, as I recall, who wondered which other country would have to rely on a charity funded by lottery money to build an essential part of its national transport infrastructure. 13 years later, the off-road sections built by Sustrans have mostly been a great success. Their use has continued to rise as national rates of cycling fell to 1.3% of trips in 2005, recovering only slightly since then. In between, local authorities across the country have failed to connect these fragments into a network worthy of the name. With more attention (and a little more money) being paid to cycling, perhaps the time has come to put the ‘National’ back into the NCN by transferring their responsibility to the Highways Agency.

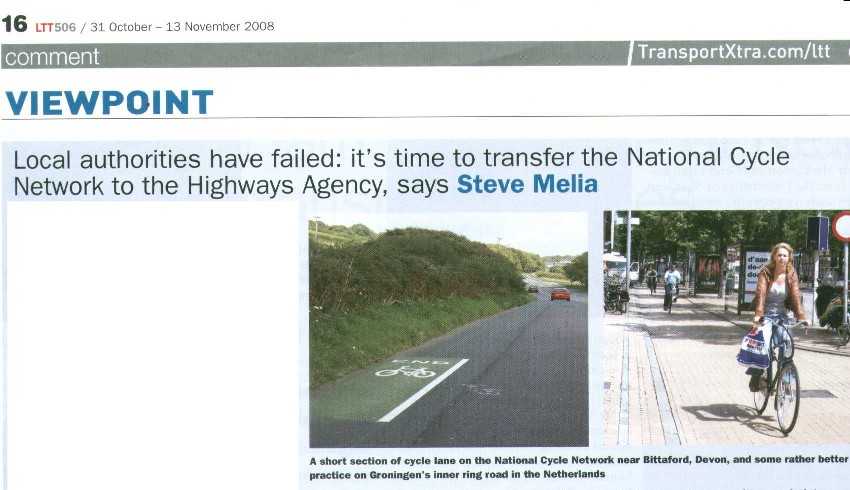

Over the past three summers I have spent several months cycling to and around the ‘cycling cities’ of Northern Europe, interviewing transport planners and studying local practice. Comparing the most successful cities with the rest, one factor stands out. Cities such as Groningen, Freiburg, Muenster and Odense, where cycling accounts for between 25% and 40% of trips, all have high quality, comprehensive, continuous cycle networks, spanning the cities and connecting to surrounding areas. Cycling between settlements, particularly in the Netherlands, is recognised as a transport as well as a leisure activity. These networks offer a much higher degree of segregation than here in the U.K., separating cyclists both from cars and from pedestrians where appropriate. Even Drachten, the birthplace of ‘shared space’ has a network of separate segregated cycle routes which would put any British town of its size to shame. In contrast, most cities in France and French-speaking Belgium, where cycling for transport is much less common, share many of the failings we see in this country.

In the successful cities ‘cycling culture’ – easier to recognise than define – has gone hand in hand with infrastructure improvements, each reinforcing the other; but culture can be changed. Seville has provided an interesting recent example where a new network and hire scheme has created a cycling culture in a city where only eccentric foreigners would have braved the traffic on a bike in the past.

Researchers in this country have struggled to demonstrate any such link between new cycle routes and area-wide increases in cycling. In most places, you do not need to cycle very far to see the reasons for this: deviations, discontinuities, pinch points and some downright absurdities, graphically illustrated in the Warrington Cycle Campaign’s Crap Cycle Lanes book and ‘Facility of the Month’ website. National and local standards on widths, junction designs and turning radii, some already lower than elsewhere in Europe, are routinely ignored wherever they conflict with other priorities. As one South Gloucestershire councillor put it recently: “they can always get off and wheel their bikes”.

Sustrans are sometimes unfairly blamed for these failings, which afflict most cycle routes in this country, not just the NCN. Sustrans’ negotiators have learned to sway with the local political winds as the price of making progress, even if this results in a route which is far from ideal. Sometimes authorities and developers simply ignore Sustrans, as happened with a major urban extension in which I have been involved. Sustrans wanted the NCN to follow a direct route through the new neighbourhood centre. The chosen route will now ziz-zag in the usual British way before joining a main road towards the city centre

The planning process, which treats each section of the NCN in isolation has produced some absurdities of its own. After 15 years of ‘interim routes’ along a narrow busy main road, in 2005, Devon County Council submitted a planning application to complete the final link in NCN route 2 between Totnes and Buckfastleigh. This angered a few locals who didn’t want cyclists and pedestrians spoiling the view from their back gardens. They found an ally in the local Crime Reduction Officer. The proposed path would make their homes “vulnerable to the prospect of crime”, she wrote, adding: “I have known of one ‘professional career criminal’ who has used a bicycle…to make a getaway”. She also objected that the path’s “remoteness” would “make users feel lonely and uneasy”. On these overwhelming grounds, the District Council rejected the application, until they were eventually over-ruled by a planning inspector.

On that occasion the landowner had at least agreed to sell. Unlike road schemes, local authorities are reluctant to use compulsory purchase for cycle paths. In some places the NCN has been diverted to by-pass a recalcitrant landowner. Local NIMBYs have bought land with the specific intention of blocking the NCN. The same tactic, when used by environmentalists against a planned motorway, ended, not surprisingly, in the High Court.

This comparison reveals an underlying problem, and one possible solution. Would right-angle turns and ‘motorists dismount’ signs be tolerated on motorways? Would our motorways have facilitated the increase in motor traffic we have seen since the 1960s if they were squeezed, interrupted and deviated like the NCN?

Beneath the veneer of environmental correctness an unspoken hierarchy operates across most highway authorities, with private vehicles and road improvements at the top. Fit-for-purpose cycle networks are likely to remain off the bottom of the scale until something changes the balance of political priorities. The transfer of local authority responsibilities for the NCN to a national body, with some reform of its planning procedure, might just help to trigger such a change.

The Highways Agency has become a strange bedfellow for many environmental groups in recent years. Though not entirely for environmental reasons, it has embraced the concept of modal shift, challenging the rose-tinted transport assessments of developers more robustly than local authorities mainly concerned with meeting housing targets.

The creation of a new ‘elite’ national unit within the Agency would improve the marginal status of cycle planning. The unit’s brief would require them to work with Sustrans, as the best authorities currently do. In other respects, it would reflect and complement the Agency’s responsibilities for motorways and trunk roads. A first taste of joined-up no-compromise, consistently maintained cycle networks would encourage many people to take up or rediscover cycling as a means of transport, raising voter expectations and councillors’ priorities. Because, of course, most cycle routes would remain a local responsibility.