![]()

Behind the public shelves in the Westcountry Studies Library in Exeter, lie three accounts of capture and delivery into slavery. Their destination was not the Americas, and their origin was not Africa, but rather closer to home. Joseph Pitts of Exeter was just 15 years old in 1678, when a pirate ship approached his fishing vessel:

“I being but young, the enemy seemed to me as monstrous ravenous creatures, which made me cry out: ‘O Master! I am afraid they will kill and eat us.’ ‘No, no child’ said my master, they will carry us to Algier and sell us.”

Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, pirates from the Barbary Coast of North Africa harassed the shipping and coastal villages particularly of Spain and Italy, but also of Devon and Cornwall, in search of plunder, both material and human.

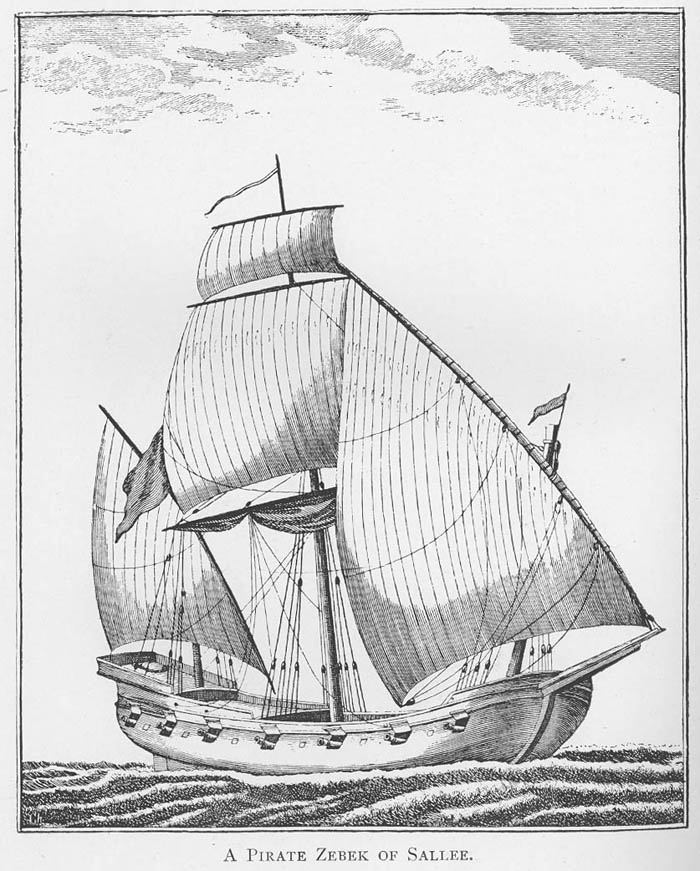

Thomas Pellow of Penryn was of a similar age in 1715 when his ship was seized by Moroccan corsairs. Attacked by a British Man of War, their ship ran aground near the port of Sallee, drowning some of the captives. Pellow himself was rescued and taken ashore to begin a life of slavery.

The story of Thomas Troughton, was reproduced some 40 years later by an Exeter man who sailed with him in 1746. Their ship, The Inspector, was itself a ‘privateer’, an officially sanctioned pirate ship, which seized French vessels and took them as “prizes” to Lisbon or Gibraltar. When they ran aground near Tangier, the crew expected assistance as “the Emperor of Morocco was at that time under a treaty of peace with the British Court”. Instead they “received the mortifying news that…a state of slavery would be our portion until the British Government had discharged an old debt claimed by the Emperor.” Their officers escaped, leaving the rest of the crew to their fate.

Some of the slaves, including Pellow and Troughton were delivered to the Emperor, and became his personal property. Captives of high rank were of particular value. On hearing that officers had escaped, the Emperor personally began the beheading of 334 people held responsible.

Other captives were sold in slave markets such as the one in Algier described by Pitts:

“There we stand from eight of the clock in the morning, until two in the afternoon (which is the time for the sale of Christians) and have not the least bit of bread allowed us during our stay there. Many persons are curious to come and take a view of us, while we stand exposed to sale; and others, who intend to buy, to see whether we be sound and healthy and fit for service. The taken slaves are sold by way of auction, and the cryer endeavours to make the most he can of them; and when the bidders are at a stand he makes use of his rhetoric. Behold what a strong man this is! What limbs he has! He is fit for any work. And what a pretty boy this is! No doubt his parents are very rich, and able to redeem him with a great ransom.”

A ransom value was an incentive to preserve the life and health of certain slaves, but most could expect only hard labour and regular beatings. Some were used as galley slaves, others in heavy building work.

Conversion to Islam was one route to better treatment. For many, including Pitts, this was an agonising decision since it was widely believed that it would bring eternal damnation. Indeed, his father, in a letter, seemed more concerned about Pitts’ religion than his freedom. Finding a ship from Topsham in the port of Algier, he met a man from Lympston who agreed to smuggle a reply, assuring his father that he remained “a Christian at heart”.

Pellow’s conversion was made under some duress, but he seems to have been less troubled by religious scruples.

Although conversion did not guarantee emancipation “it is looked on as an infamous thing for any patroon [owner] in some few years after they have turned to deny them their liberty”. Pitts was bought and sold several times until his final patroon took him on a pilgrimage to Mecca, where he was granted his liberty. Pitts says of this patroon: “I had a great love for him even as a father but still this was not England and I wanted to be at home.”

But even after emancipation, attempting to return home could lead to execution. For Pitts, a chance meeting in a barber’s shop in the Turkish port of Smyrna was the first step to escape:

“there was then an English man shaving, whose name was George Grunfell of Deptford. He knew me not otherwise than a Turk, but when I heard him speak English, I ask’d him whether he knew of any of the West-parts of England to be in Smyrna? He told me of one, who he thought was an Exeter man, which when I heard, I was glad at heart.”

After four years of negotiations, the surviving crew of The Inspector, including Troughton and his friend from Exeter, but excluding the 28 who had converted to Islam, were eventually released on payment of a ransom. Pellow spent 23 years in the service of the Moroccan Emperor, during which time he married and fathered a child. Only after the death of his wife and daughter did he also decide to escape and return to Penryn.

Pitt’s journey home after 15 years nearly ended on his first night back in England, when a press gang threw him into prison for refusing to enlist in the navy. Only the intervention of an aristocratic patron enabled him to return to Exeter where:

“The house soon filled with the Neighbourhood, who came to see me. What joy there was at such a meeting, I leave the reader to conceive of, for ‘tis not easily express’d. The first words my father said to me were ‘Art thou my son Joseph?’ with tears. ‘Yes father, I am’ I said.”